1.2 Preserving Heritage: From an Analogue Past to a Digital Future

1.2.1 Understanding Material Culture

Climate change, physical damage, mass tourism, the illicit trading of antiquities, as well as war and political conflicts have made cultural heritage more vulnerable. Therefore, the preservation of material culture has become a top priority across the globe. The study of material culture, i.e. material objects produced by people but also natural objects and human remains, provide a glimpse to societies of the past and the present. In many cases, material culture is the only evidence we may have to understand these societies, especially when there is no written evidence or when it is fragmentary. For example, for the prehistoric period, we are trying to decipher the meaning of material culture based on its context, parallels, and even more recent ethnographic evidence. It is an act of interpretation since meaning is always relative to the individual, society, or culture that produced it and to the researcher that studies this material. According to Prown (1988, p. 19):

...objects made or modified by man reflect, consciously or unconsciously, directly or indirectly, the beliefs of the individuals who made, commissioned, purchased, or used them and, by extension, the beliefs of the larger society to which they belonged.

The American art historian, Bernard Herman, has suggested two approaches to the study of material culture: object-centred and object-driven (1992). In the former, the focus is on the material objects themselves, including for example, their materials, size, colours, textures, uses and provenance. On the other hand, an object-driven approach explores the meaning of these objects, including their relationship to people and cultures, their use in certain contexts, as well as their changing meaning within particular social and cultural practices. However, objects are not only 'waiting' to be interpreted but they also have agency (Jones and Boivin 2010); 'they produce effects, because they make us feel happy, angry, fearful, or lustful' (Hoskins 2006, p. 76). Thus objects have an impact that goes beyond their material status. Remember, for example, the destruction of cultural artefacts/sites by ISIS, we saw in the previous lesson, in an attempt to eliminate the symbolism and meaning carried by the objects; in that case, Syrian cultural heritage represented a false religious belief.

It should also be noted that objects often obtain uses and meanings beyond those that were originally intended by their creators. In that sense, material objects have a biography that continues to be formulated by the 'sum of the relationships that constitute it' (Joy 2009, p. 552). This means that an object may change several uses, meanings, and contexts during its life through its social interactions and uses; for example, it may start as a utilitarian tool in a Neolithic house and end up exhibited in a museum. During this trajectory, the object will accumulate histories related to the people and contexts in which it was used, including the neolithic household in which it was used and maintained, its recycling when it was not anymore used as originally intended, the archaeologists who unearthed it, a conservator, a museum curator who put it together with other objects in a museum display etc.). As many scholars argue (e.g. Harrowell 2016) destruction, the same way as natural decay, is also part of a site’s/object's biography, and therefore, potential reconstructions (especially in the case of negative heritage) should be approached with caution, as they construct new narratives that often serve particular political agendas.

|

|

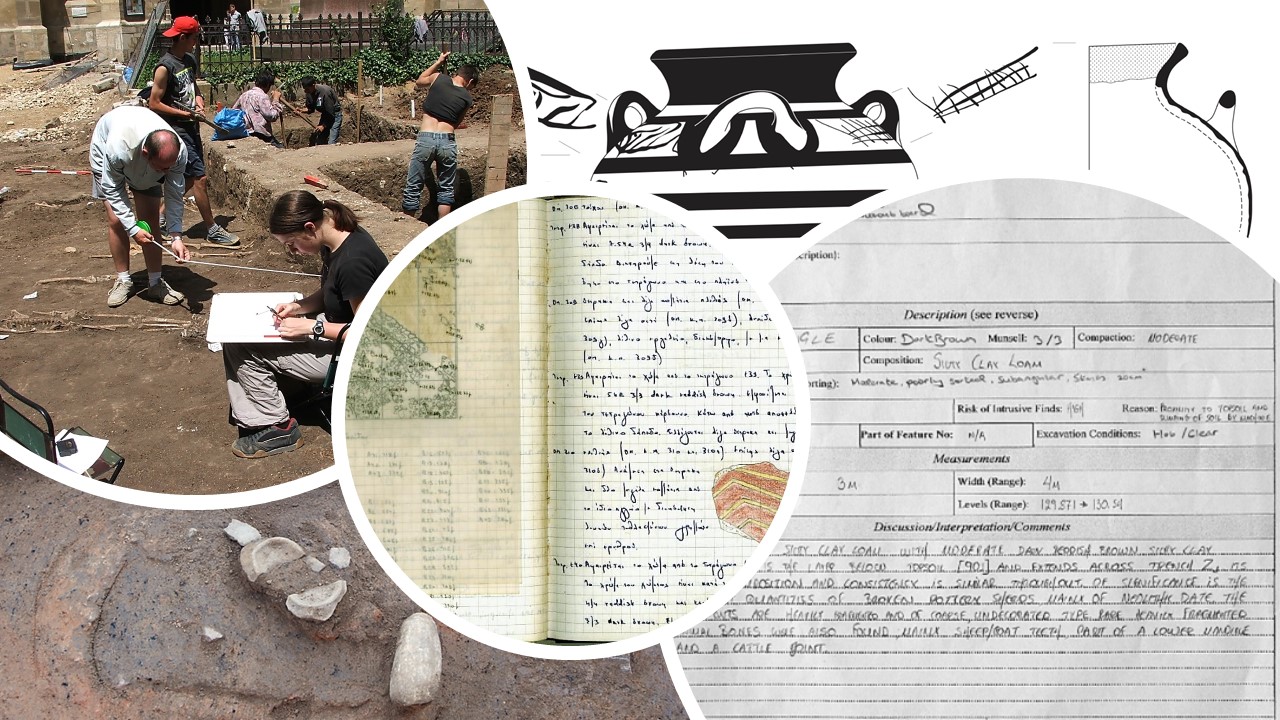

Examples of Conventional Recording in Archaeology: |

Such visual media are mainly used to support the production of knowledge, and also to communicate it to the public. However, the system of signs used often makes these mechanisms inaccessible to the inexperienced and untrained receptors. This is also a form of Authorised Heritage Discourse (see section 1.1), which limits the audience of such products and authorises specialists in producing this knowledge. For example, textual recordings include a certain level of scientific jargon and conventions that are not universally applied and understood. Photographs on the other hand, only record a moment in time, while the drawbacks of the medium itself and its use by the operator result in altered views of the captured scenes. Drawings are equally subjective as the way that the evidence is illustrated highly depends on the individual perception and his/her skills. Therefore, all recording mechanisms are subjective means of representation, which alter reality, and provide a distorted reflection of the past; therefore through a process of reduction the complexity and diversity of the material world is diminished. Based on this, we should think of the people that never had the chance to visit a particular site (or experience and object) and embody themselves its three-dimensional qualities in order to create a narrative and structure understandings (Tilley 1994, pp. 27-33), and therefore can only get that feeling through the products of the various recording mechanisms.

Recent advances in the technologies employed in archaeological fieldwork and cultural heritage documentation direct the recording of the evidence towards a three-dimensional approach. Laser scanners, photogrammetry and Reflectance Transformation Imaging are methods - among many - which are increasingly applied to cultural heritage datasets in an attempt to capture more information than conventional recording. The fact that these methods capture the three-dimensionality of the evidence, it does not mean that the record will retain its original characteristics and that the process of digital reconstruction will provide more coherent understandings of the outputs. The following sections will cover these in more detail.

In this exercise, you are asked to compare the three-dimensional properties of an object as handled and the properties of the same object when observed through a photograph. To do this follow the steps below:

|

| A photograph of a coaster and the coaster observed by handling (Click to enlarge the figure) |

- Find an everyday object that you are often using.

- Use your mobile phone or camera to take a photograph.

- Look at the photograph and write down the three-dimensional properties of the object. We will cover these in the following section, but you should first try to put on paper as many 3D characteristics you can think of. Bear in mind that three-dimensionality is not only defined by the shape of an object.

- Now take your object in your hand and start observing it.

- Which senses did you use during the observation? How did your observation differ in comparison to your photo?

- Write down the object's three-dimensional properties as observed in the second time.

- Compare the two lists. Do they differ? Are there three-dimensional properties missing from the two lists?

References

- Edgeworth, M. (2003). Acts of Discovery: An Ethnography of Archaeological Practice. BAR International Series 1131. Oxford: Archaeopress.

- Harrowell, E. (2016). Looking for the Future in the Rubble of Palmyra: Destruction, Reconstruction and Identity. Geoforum 69, 81-83. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2015.12.002

- Herman, B. L. (1992). The Stolen House. Charlottesville and London: The University Press of Virginia

- Hoskins, J. (2006). Agency, biography. And objects, In Tilley, C. et al. (eds.) Handbook of Material Culture, pp. 74-84. London: Sage Pub.

- Jones, A., & Boivin, N. (2010). The malice of inanimate objects: material agency, In. Hicks, D. and Beaudry, M. S. (eds). The Oxford Handbook of Material Culture Studies, pp. 333-351. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Joy, J. (2009). Reinvigorating object biography: reproducing the drama of object lives, World Archaeology 41(4): 540-556.

- Prown, J. D. (1988). Mind in matter: An introduction to material culture theory and method. In Robert Blair St. George (ed.) Material Life in America, 1600-1860, pp. 17-37. Boston: Northeastern University Press.

- Tilley, C. (1994). A Phenomenology of Landscape. Places, Paths and Monuments.Oxford: Berg.

Further Reading

- Hicks, D. and Beaudry, M. S. (2010). The Oxford Handbook of Material Culture Studies. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Gell, A. (1998). Art and Agency: An anthropological theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Latour, B. (1999). Pandora's Hope, An essay on the reality of science studies. Cambridge: Harvard University Press