Unit I: Introduction to Social Justice in the Digital Humanities

1.3 The Prison Writer as Witness: The American Prison Writing Archive

This case study is written by Professor Doran Larson. The page is designed by Anna Villarica.

Introduction

From a cell in Alabama, Donald Hairgrove writes, “Through silence, isolation, ignorance and indifference  society has allowed and even promoted the steady growth of this criminal justice bureaucracy.” Then he lists things he must do to remind himself that he’s still a human being while confined in that state’s notoriously violent facilities. Imprisoned in Indiana, Valjean Royal documented the serial rape she endured as a transgender woman and how she found the strength and resources to resist while maintaining her Christian faith: “I've gained a light of wisdom from the pain of abuse. A light I want to share with others so they can ‘see’ the better choices they can make, even in the dark places.” Georgian Jamil Hayes describes prison units under COVID lockdown, the absence of health care and resulting tensions that lead to “C.O.s shooting inmates with paint ball guns loaded with pepper spray. It’s like a war zone.”

society has allowed and even promoted the steady growth of this criminal justice bureaucracy.” Then he lists things he must do to remind himself that he’s still a human being while confined in that state’s notoriously violent facilities. Imprisoned in Indiana, Valjean Royal documented the serial rape she endured as a transgender woman and how she found the strength and resources to resist while maintaining her Christian faith: “I've gained a light of wisdom from the pain of abuse. A light I want to share with others so they can ‘see’ the better choices they can make, even in the dark places.” Georgian Jamil Hayes describes prison units under COVID lockdown, the absence of health care and resulting tensions that lead to “C.O.s shooting inmates with paint ball guns loaded with pepper spray. It’s like a war zone.”

These writers’ witness is hosted by The American Prison Writing Archive, the first fully searchable digital archive of non-fiction and poetry by incarcerated people writing about their experience inside US prisons and jails today. Initiated in 2009 by Hamilton College literature professor Doran Larson’s call for essays for a book collection, Fourth City: Essays from the Prison in America (2014), the APWA is the result of incarcerated people continuing to write beyond that book’s deadline. Legally confined writers rushed the gates of analog publication and onto a digital platform, resulting in a living archive of prison witness.

Rationale for the project

At just under two million, the people living and working behind bars in the US constitute a major metropolis. This is a prison city not only in sheer numbers but in the coherency of literary witness to the human experience of prison conditions. These writers offer the most extensive corpus of experiential, grounded writing and knowledge about US confinement in our time.

The APWA secures prison witness’ place in our understanding of the carceral state. Contributions from Rikers Island to San Quentin and everywhere in between have established the APWA as a central hub of prison witness for the academy, journalists, activists, civic leaders, system impacted communities and family members. The APWA is responsive to the needs and ideas and aspirations of both the confined and the families and communities they come from, all newly enabled to see and share the suffering, trials, challenges, and freedom dreams that the mass prison seeks to silence.

|

|

Letter envelope from writer Larry E. May |

By gathering the human stories emerging from prison facilities across the nation, the American Prison Writing Archive helps us to measure the full human costs of American legal order, placing imprisoned people at the vanguard of mapping the Prison City that anchors and perpetuates both legalized inequality and the carceral state. The digital presence of these authors stands in direct resistance to the centuries-long efforts of prisons and jails to silence their wards. They thus join a 200-plus year canon of testimony from incarcerated Americans testifying to the utter failure of the prison to achieve constructive ends.

The APWA was initiated, developed and sustained at Hamilton College for over ten years with the support of Hamilton College and the National Endowment for the Humanities. It is now housed at Johns Hopkins University and supported by Johns Hopkins and a major grant from the Andrew Mellon Foundation. The APWA currently hosts over 3,300 essays, from forty-eight states, over four hundred prison facilities, and includes 1,099 authors. It grows by approximately seventy new works each month. Essays run from one-page cries for help from the unceasing light of isolation cells, to hip-hop inflected shout outs of warning to kids in subjugated communities, to research-based policy critiques, and more.

|

Click on the hotspots to find out more about the works of the authors. |

In literary testimony from across the nation, we see the prison population emerge as a nearly inexhaustible resource for first-person reassessment of US criminal legal practices, who they target, and their effects on individuals, families, and communities. The counter-narratives in the APWA open the mass prison to humanist scholars and students, the broad public, lawmakers, and the families of incarcerated people. They breach the “silence, isolation, ignorance and indifference” that, as Donald Hairgrove claims, have entombed a carceral metropolis. The APWA poses a singular opportunity for the legally confined to play a vital role in reshaping collective wisdom about carceral experience.

The aim of the APWA is to make prison witness widely accessible, so that when scholars, journalists, policymakers and the public discuss incarceration, they must confront the testimony of those inside. With a current word count equivalent to over forty-one percent of all known North American slave narratives, perhaps the most daunting fact about the APWA is that it has been drawn primarily from a single, quarter-page call for essays in the monthly pages of Prison Legal News. The APWA, even at its current rate of growth, is mounting one of the largest bodies of witness literature on earth, thus documenting the tens of thousands of complex, thriving, damaged, yet resistant lives being led in lockups across the US today, and their collective critiques, experiences, and aspirations.

The APWA has enabled projects that offer unprecedented glimpses into the lived experience of punishment: “The Zo,” from The Marshall Project, presents testimony to the institutionalized disorientation that imprisoned people endure and to their efforts to adapt, respond, and resist; Josefine Zieball’s “Queer and Trans Prison Voices: A Podcast Archive on Prison Abolition” offers the voices of a population living at existential odds with the cultures of the institutions where they are housed; undergraduate and graduate classroom use and theses have illuminated the common narratives that official records obscure; and a network of over two hundred volunteers transcribing hand-written essays and tagging essay contents across four continents—in classrooms, community centers, libraries, and private homes—gives evidence of how the APWA can draw the support of people across borders and demographics.

|

The APWA has provided the basis for other forms of storytelling related to carceral life. |

Why digital humanities

The APWA is among the increasing number of DH projects that use the digital as a way to challenge social injustice. Prisons are places where social inequalities are both manifest and anchored. People within face abuse and marginalisation, away from the eyes of the wider public. Their stories have largely been told for them - by journalists, researchers, and the legal system, among others. The grassroots, bottom-up ethos of the APWA has bypassed pre-set research or data-gathering agendas, providing an open call for legally confined people to tell the stories they choose to tell. These writers cast off their positions as objects of study and claim the power of narrative witness to their lives, their conditions, and to their essential roles as collective creators of knowledge from inside the grip of the carceral state.

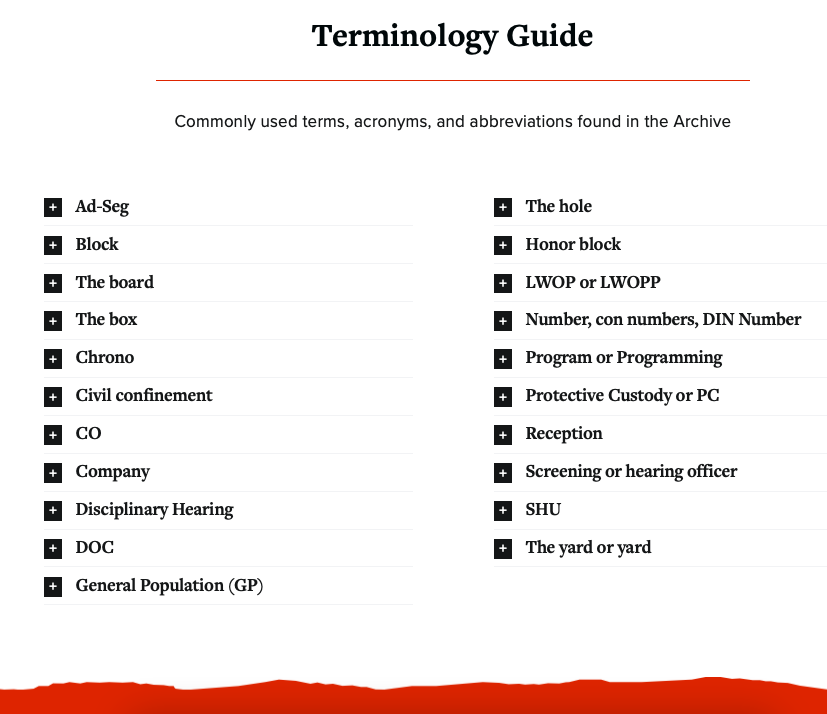

The Archive is guided by the intentions of writers inside carceral institutions. People who have been in or are currently in the prison system contribute as consultants on the project. In addition, the writers themselves provide the contents of the APWA’s metadata. Search fields include the state of origin, keywords, author and date, and are supplemented by author ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, religion, and veteran status. The resulting faceted and word searches allow readers to find information quickly. This also allows the diversity of the prison metropolis to be reflected to the reader. A ‘Terminology’ section on the site gives a guide for readers of the meanings of prison-related terms commonly found in the essays, and a ‘Saved selections’ makes it possible for readers to bookmark essays and curate them.

The Archive is guided by the intentions of writers inside carceral institutions. People who have been in or are currently in the prison system contribute as consultants on the project. In addition, the writers themselves provide the contents of the APWA’s metadata. Search fields include the state of origin, keywords, author and date, and are supplemented by author ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, religion, and veteran status. The resulting faceted and word searches allow readers to find information quickly. This also allows the diversity of the prison metropolis to be reflected to the reader. A ‘Terminology’ section on the site gives a guide for readers of the meanings of prison-related terms commonly found in the essays, and a ‘Saved selections’ makes it possible for readers to bookmark essays and curate them.

As seen below, the interface includes the scans of the original submissions next to the text transcripts. These original scans reflect the conditions of composition and hint at the unequal distribution of opportunities in the prison system (Larson, 2021, para. 35). Some submissions were sent as typed documents printed off a computer, while others were written with a pen or pencil, reflecting that while some have access to technology, others do not. Some pieces were also published in newsletters, indicating support and resources outside. These are not enjoyed by all.

|

Use the slider above to see the difference between the original submissions and how they are presented on the interface. |

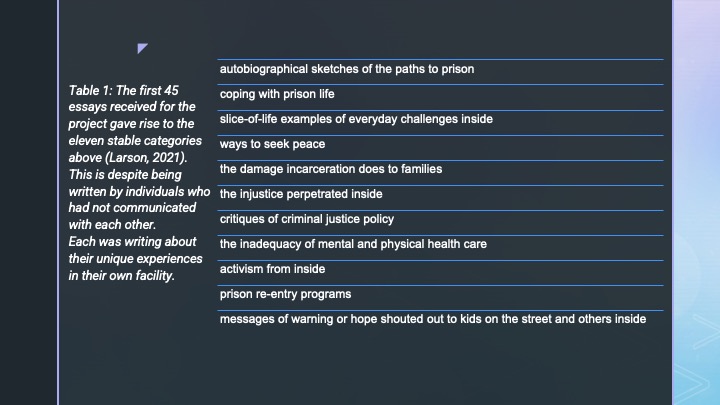

Larson also suggests in a 2021 essay for Digital Humanities Quarterly that DH as a methodology can facilitate social justice efforts for people in carceral institutions. He relates questions regarding balancing ‘addressing mass incarceration as a statistical fact - as a data set - and/or as a human and humanly articulated condition experienced and documented as discrete individuals’ (Larson, 2021, para. 4) to the debate between distant reading and close reading as methods. Purely computational approaches may run the risk of reducing the testimony of incarcerated individuals to data points, while close reading an individual piece may fail to reveal the larger context it is part of. Thus, the approach Larson (2021) advocates for reading prison witness content is what he calls cellular reading. This is reading at a ‘proximal’ distance (para. 14), the middle range which falls between distant reading and close reading. Each written piece is a cell, like in a body or prison architecture. While each piece is a singular statement, it offers ‘context-dependent representative testimony for a collective body’ (para. 2), each piece stands among ‘witness borne by individual human beings who are also exemplars among a mass population’ (para. 13). Throughout the corpus of prison narratives, common themes are found (See Table 1 below). While these ‘’typical’’ moments across the texts carry authority, at the same time ‘each text remains absolutely authoritative regarding the experience, anger, aspirations, hope or hopelessness of its author’ (para. 14). In other words, while computational analysis makes the discovery of themes easier and may become for readers ‘the basis for focused advocacy’ (para. 22), focused reading is also necessary to get a full sense of the unique lived experiences of individuals.

|

| The table shows the common categories found in initial prison witness essays |

From invisibility to visibility

At the end of her best-selling book, The New Jim Crow, Michelle Alexander writes, “Isolated victories can be won—even a string of victories—but in the absence of a fundamental shift in public consciousness, the system as a whole will remain intact.” (Alexander, 2010, 234). In 2016, Marie Gottschalk seconded Alexander’s conclusion and underscored the “invisibility of millions” of imprisoned from the public sphere:

The slave narratives of the antebellum period, which graphically rendered the physical pain that slaves suffered and made it widely visible, helped to propel the abolitionist cause. Today, what happens in prison stays mostly in prison, making it harder to draw connections in the public mind between justice on the inside and justice on the outside. The ability to identify with an offender—or not—is a key predictor of why people differ in their levels of punitiveness.(Gottschalk, 2016, 274)

The American Prison Writing Archive is an effort to do for incarcerated people what America’s slave narratives did for enslaved people: through representative writers, to dismantle public propaganda about who de-legalized people are, the nature of the regime under which they live, and the disastrous personal, communal, and social effects of this regime. It is an effort to do for those legally confined in the US today what witnesses at truth and reconciliation commissions do for themselves and for future generations: to give faces and voices to those on the receiving end of state-sponsored violence, exploitation, and inequality, and to make evident the irreplaceable human stories that witnesses bring to any thinking or public debate about ways to move forward.

To enable fundamental change in carceral policies and practices, and to abandon imprisonment as the default answer to poverty, mental illness, and legacies of subjugation, public perceptions of incarcerated people need the kind of transformation that images of the targets of police violence are undergoing today. The writers in the APWA are already evoking such transformation in the minds of students in classrooms from Berkeley to New Haven, from Baltimore to Santa Clara. In Iowa, California, Maryland, Texas, Connecticut, Indiana, Florida, Idaho, and other states, students are working in and for the Archive as well as doing research and writing based on its holdings. The effects of such work can be profound. As one student concludes, “No other group of individuals is more knowledgeable about the realities of incarceration and the toll it imposes.”

![]() Exercise: Curation workshop

Exercise: Curation workshop

Curating essays is a valuable experience for students, educators, researchers and casual readers of prison witness. In searching and grouping essays thematically, links are drawn between individual testimonies. It is possible to curate a collection for specific themes, or to help tell stories that may be overlooked. Through curated collections, common themes and narratives come to light. For readers of the website, curated collections are another way to locate essays. Use the template below to curate prison witness testimonies as others have done.

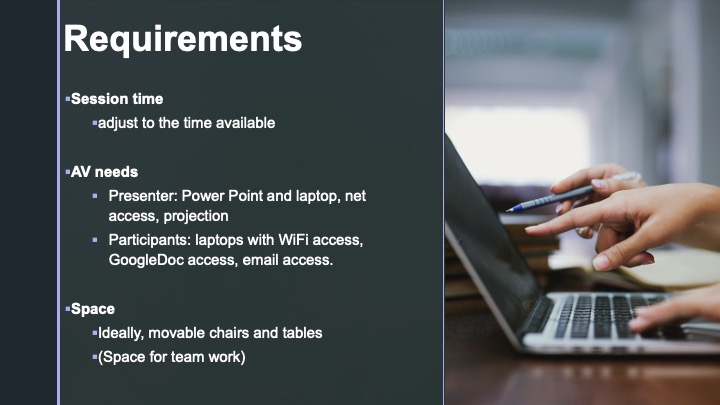

-

Introduction(s)

-

Get prisonwitness.org on screen

-

Tour of APWA pages

- Try keyword searches using the search interface (Home> Explore the Archive)

- A guide to the search interface is at the end of this page

- Explore individual essay pages (by clicking on an essay title)

- Try to copy and paste essay content, download PDFs and add (+) to Saved Selections

-

Show some sample curations

-

Participants divided into curation teams

- Time for self-introductions

- Brainstorming on curation topics and choosing one as a team

- Table 1 above provided common themes in prison witness corpus that could provide starting points for brainstorming

-

Presenter consults with each team to refine topics

- Assures that critical numbers of relevant search results exist

- Avoid redundancies with other teams and existing curations

- Avoid broad search topics (e.g. 'language') whose subject thread may be indiscernible; choose specific, concrete topics (e.g. medical negligence, hygiene, visitation)

-

Create google.doc for each team to gather their selections

-

Formatting curations with the following information

- Author name

- Essay or poem title

- URL

- Copy (from APWA transcripts) essay, poem, or relevant excerpts

-

Teamwork time

- Presenter can walk around to answer questions, make suggestions etc.

- Please tag any instance in which you copy over a whole essay

- We need to know this in order to respect the copyright agreement with APWA authors

- Review of work and sharing of GoogleDocs with dlarson@hamilton.edu

Guide to the search interface

Below you will find the various search functionalities as well as the different forms of navigation. Have participants try them out.

|

Click on the hotspots to find more information on the different ways of locating prison witness essays.

|

Author Bio*:

Doran Larson is Edward North Professor of Literature at Hamilton College. He led a writing workshop inside Attica Correctional Facility for ten years and has organized two college programs inside New York State prisons. The author of Witness in the Era of Mass Incarceration (2017), and editor of Fourth City: Essays from the Prison in America (2014), his book Inside Knowledge: Incarcerated People on the Failures of the American Prison, will appear in 2024. He founded and co-directs the American Prison Writing Archive.

Designer Bio*:

Anna Villarica is a research assistant on the #dariahTeach project. She is a junior lecturer at Maastricht University currently teaching courses on design thinking, digital transformations, the philosophy of technology, research skills, and museology. She received her MA in Media Studies Digital Cultures from Maastricht University and her BA in Communications and New Media from the National University of Singapore. While she does not specialise in anything (yet), she loves all things digital and is always learning and creating.

*Bio and affiliation are accurate at the time of writing

References

- Alexander, Michelle. The New Jim Crow. New York: The New Press, 2010.

- Crabapple, Molly, and Williams, Michael. “The Zo: Where prison guards’ favorite tactic is messign with your head.” The Marshall Project. February 27, 2020. https://www.themarshallproject.org/2020/02/27/welcome-to-the-zo.

- Doolittle, Patrick. "’The Zo’: Disorientation and Retaliatory Disorientation in American Prisons.’” Bachelor’s thesis, Yale University, 2017.

- Fourth City: Essays from the Prison in America. Edited by Doran Larson. East Lansing, Michigan: Michigan State University Press, 2014.

- Gottschalk, Marie. Caught: The Prison State and the Lockdown of American Politics. New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2016.

- Hairgrove, Donald. “A single unheard voice.” The American Prison Writing Archive. Johns Hopkins University, July 12, 2015. https://prisonwitness.org/apwa-essay/a-single-unheard-voice/.

- Hayes, Jamil. “Being incarcerated during the Covid-19 pandemic.” The American Prison Writing Archive. Johns Hopkins University, August 20, 2020. https://prisonwitness.org/apwa-essay/being-incarcerated-during-the-covid-19-pandemic/.

- Larson, Doran. "Prison Writer as Witness.” Digital Humanities Quarterly 15, no. 3 (2021): 0-11. Accessed April 26, 2023. http://www.digitalhumanities.org/dhq/vol/15/3/000571/000571.html.

- Royal, Valjean. “Survivor testimony: Finding light in a dark place.” The American Prison Writing Archive. Johns Hopkins University, 2008. https://prisonwitness.org/apwa-essay/survivor-testimony-finding-light-in-a-dark-place/.